Rethinking Stereotypes About Asian American Students Through Learning History

Jinhee Kim, Assistant Professor, Department of Elementary and Early Childhood Education, Kennesaw State University/ President, Resono Children Center, Inc.

and

Sohyun An, Associate Professor, Department of Elementary and Early Childhood Education, Kennesaw State University

“They merely assume I’m quiet, study a lot, and probably play a musical instrument. I’m not really saying that none of these are true, but everyone classifies me as a stereotypical Asian person.” (Emily; all names used are pseudonyms)

Last summer, a small group of Asian American high school students participated in the Asian American Youth Leadership Initiative, in which they sought to develop a healthy racial/ethnic identity and civic agency through an exploration of Asian American history and current issues. During a discussion session, Emily, a Chinese American student, shared the above comment. Other students also shared their experiences encountering stereotypes about Asian American students, such as being assumed to be studious, high achieving, quiet, and good at math. Although seemingly flattering, these stereotypes deny the fact that not all Asian American students are high-achieving, successful students, and they ignore the challenges and struggles Asian American students encounter every day.

The Asian American Youth Initiative was developed by Resono Children Center, Inc., a nonprofit organization serving immigrant children and their families in Georgia, U.S. Jinhee, the director of the center, and Sohyun, a university professor in the region, collaborated to provide a space where Asian American youth could critically examine racial stereotypes and prejudices affecting them and develop the civic agency to challenge the stereotypes.

Geographic Context for the Initiative

Historically, the American South has been viewed as isolated and biracial (i.e., White or Black). Over the last two decades, however, Asian immigrant communities and Asian ethnic economies have grown rapidly in the South, bringing about demographic and cultural changes. In fact, Georgia is one of the top five states in terms of Asian American population growth. Schools in Georgia, however, are struggling to serve the growing Asian American student population. Many Korean American students in Georgia felt marginalized in school and believed their teachers were unconcerned about the racism they experience. Often stereotyped as “model minority” students who do well in school and thus need no educational support, Asian American students and their educational needs and challenges are often ignored.

In this context, we developed the Asian American Youth Leadership Initiative in order to help Asian American youth in Georgia examine stereotypes about Asian Americans critically and explore ways to challenge those stereotypes. A two-day session covered three overarching themes: 1) challenge the stereotypes, 2) explore Asian American history and current issues, and 3) collaborate with the local community to design an action plan for change. We recruited participants through various media that reached the local Asian American communities. Five high school students (three Chinese Americans and two Korean Americans) living in the Atlanta metro area participated in the initiative. While we had hoped for more students to be involved, we were impressed by these students’ passion for a more inclusive and democratic society. This was the first program for Asian American youth empowerment in the region.

Challenging the Stereotypes

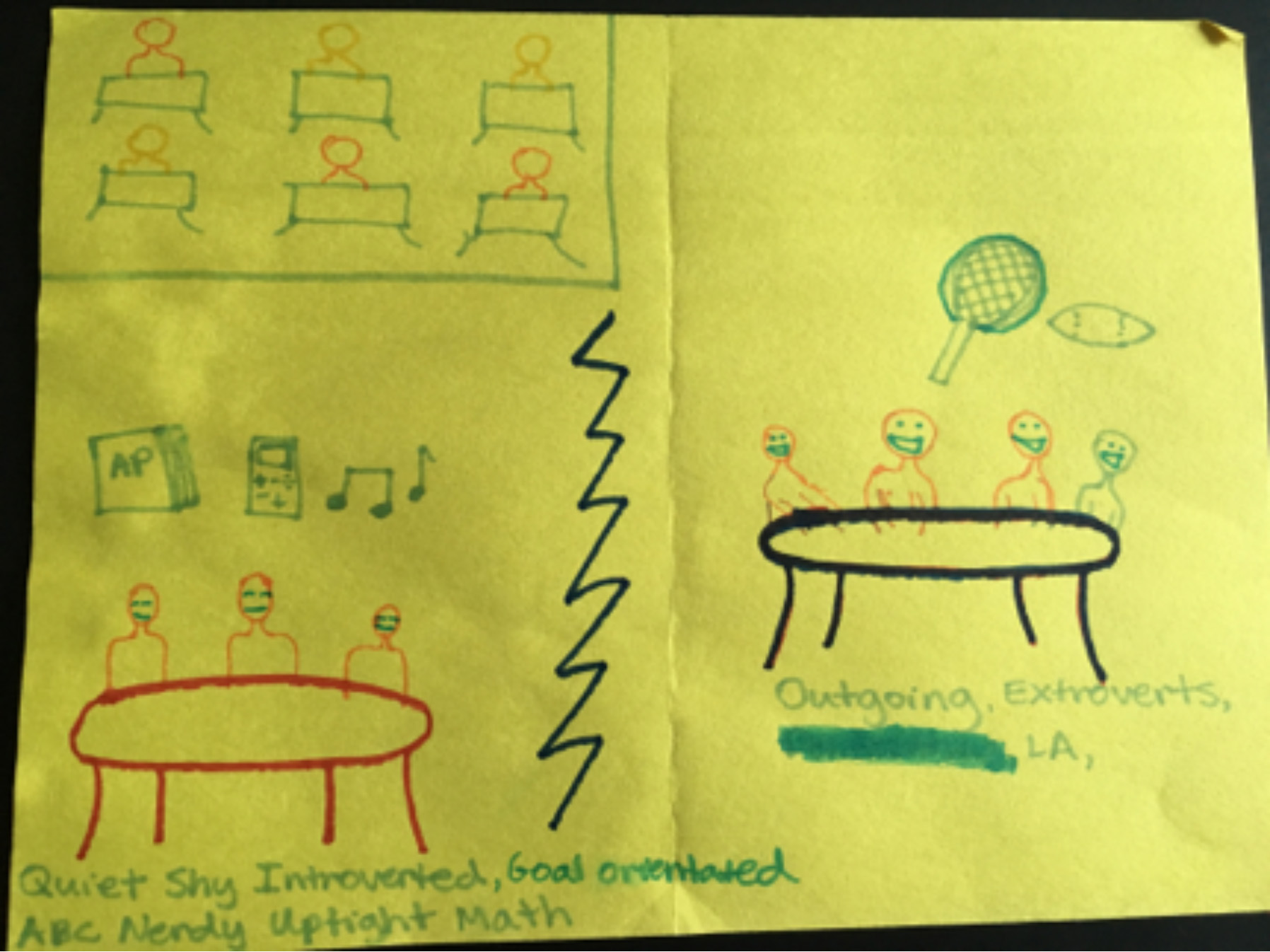

Photo 1

The students engaged in various activities that helped them critically examine Asian stereotypes. Kylie, a Korean American student, drew contrasting images of Asian American students vs. European American students (see photo 1). Kylie explained that Asian American students are often viewed as quiet, shy, nerdy, which she viewed as negative compared to the images of Whites as outgoing and extroverted. Sara, a Chinese American student, drew diverse images of Asian Americans as a way of challenging a single dominant image of Asian Americans (see photo 2). Chloe, who emigrated from Korea to the United States when she was in 8th grade, talked about racial slurs that had been directed toward her:

photo 2

"Some students were saying something racist towards me, especially because I moved to the U.S. not so long ago. I was hurt a lot. . . . At first, I told them not to say that stuff to me, but they would not stop, but made fun of the fact I was telling them to stop."

After exploring personal experiences with anti-Asian stereotypes, we invited two Asian American spoken word artists to perform for the group. Their poetry and comedy were based on their own personal experiences with racism and stereotypes. After the performances, the students and the artists engaged in a discussion about racism and stereotypes. The artists explained how they and their fellow artists challenge stereotypical images of Asian Americans through different artistic visions.

Another guest speaker was Dr. Steven Kim, a surgeon at a local hospital who grew up in the Southern United States as one of only a few Asian American students in his school and community. He shared his story about how he navigated the anti-Asian bias and prejudice he experienced from his peers and teachers. The students found that Dr. Kim’s story was closely aligned with their own lives and the struggles they were currently facing. They had many questions, and the ensuing discussion was rich, fun, and empowering. He suggested that the youth start with what they have, such as their abilities and strength, and discussed how they can overcome stereotypes, telling them, “Passion drives decisions.”

Exploring Asian American History and Current Issues

photo 3

The program also provided an opportunity for the Asian American youth to hear stories of Asian Americans that remain untold in school history curricula (see photo 3). Despite the 150-plus-year history of Asians in the United States and decades of multicultural efforts, Asian Americans and their stories are still almost invisible in school curricula. Discussions about race in the United States have continued to be constructed based on a white-black dichotomy, in which Asian Americans are “forever foreigners.” Despite decades of multicultural efforts, official school curricula are still largely Eurocentric, such that Asian American histories and perspectives are not included or acknowledged. When Asian Americans are included in U.S. history curricula, they are often presented as a model minority and are lumped together as a successful, hardworking, compliant, and passive minority.

In order to counter the dominant narrative reflected in school curricula, students were introduced to excluded, silenced stories of Asian Americans who actively fought against injustice and contributed to the building of the United States. For example, the students learned that Chinese immigrants built transcontinental railroads, Japanese Americans fought overseas during World War II while their families were interned at home, Asian laborers worked on farms and contributed to agricultural production, and many Asian Americans today are driving U.S. economic growth in Silicon Valley and beyond. The youth participants also learned about Asian Americans’ fight against anti-Asian immigration laws, the segregation of Asian American children in schools, and the exploitation of Asian Americans in the workplace. They learned about the Asian Americans who joined other marginalized groups in organized activism and launched the “Yellow Power” movement, fighting for equality during the Civil Rights Movement.

Exploring these seldom told stories of Asian American struggles and their fight against inequality helped the youth participants challenge and criticize popular stereotypes of Asian Americans. One student stated in the post-survey, “It was definitely an eye-opener. I learned a lot of new facts about Asian Americans’ untold history in the U.S.” Other students shared during the discussion how empowering they found it to know that “We [Asian Americans] were here for a long time; we made and are still making contributions to our country.”

Collaborations With the Local Community

Social stereotypes and inequality have to be confronted openly and discussed deeply among community members. We hope that the students involved in this program developed a critical understanding of the United States’ past and present through the program and that they will act to bring about change. At the end of the initiative, Thomas, a Chinese American student, noted, “While growing up in an Asian American Community, I have never had an opportunity like this. . . . I didn’t know how to embrace my culture before.” He appreciated the opportunity to dig deeper into what it means to be an Asian American and what he can and should do to make American society more inclusive and just.

Paralleling the efforts of multicultural education in school systems, community-based programs can fill gaps to promote healthy racial and cultural identities, develop a critical understanding of unequal discourses and practices, and foster civic agency to make changes for the better. Through the program, we found that the synergistic collaboration between a nonprofit organization and the local community could create a strong foundation from which priceless resources for all community members can be identified. Each society has powerful resources available to build a more respectful community. For example, through collaborations with local experts and leaders, minority youth groups can build up their networks, sharing their challenges and struggles with mentors who have already walked similar paths. Given active participation in the creation of supportive environments, the community can rethink stereotypes and unequal discourses and learn to embrace everyone.

Resources

Chang, R. S. (1993). Toward an Asian American legal scholarship: Critical race theory, poststructuralism, and narrative space. California Law Review, 19, 1243-1323.

Choi, Y., Lim, J., & An, S. (2010). Marginalized students’ uneasy learning: Korean immigrant students’ experiences of learning social studies. Social Studies Research and Practice, 6(3), 1-17.

Heilig, J. V., Brown, K., & Brown, A. (2012). The illusion of inclusion: A critical race theory textual analysis of race and standards. Harvard Educational Review, 82(3), 403-424.

Lee, S. (1996). Unraveling the “model minority” stereotype: Listening to Asian American youth. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Nieto, S. (1992). Affirming diversity: The sociopolitical context of multicultural education. New York, NY: Longman.

Tuan, M. (1999). Forever foreigner or honorary whites? The Asian ethnic experience today. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Wu, F. (2002). Yellow: Race in America beyond black and white. New York, NY: Basic Books.