From Fathers to Fathers:

The Story of Fatherhood and Caregiving in a

Rio de Janeiro Community

By Letícia Serafim and Mohara Valle, Promundo

Better maternal and child health outcomes, greater cognitive development, the prevention of domestic violence, and the promotion of gender equality—all in addition to improved health and well-being for men. These are just some of the positive effects of men’s equitable involvement in the care and upbringing of their children, according to the first-ever State of the World's Fathers report,1 which was released in June 2015 by the MenCare Campaign and co-ordinated globally by Promundo.

The inequitable division of unpaid domestic and care work around the world, however, continues to pose a major barrier to men’s full involvement at home and its corresponding benefits for individuals, families, and societies. According to the report, while women today make up 40% of the formal global workforce and 50% of the world’s food producers, men’s unpaid caregiving has not changed correspondingly. Globally, women continue to spend between two to 10 times longer caring for a child (or older person) than men do.

For some fathers in Rio de Janeiro’s Vila Joaniza community, however, this is no longer the case. Cleber Leonardo Ramos is one man who is defying the norm. He is father to 8-month-old Isabela and stepfather to 14-year-old Victoria and 4-year-old Livian, who are the daughters of his wife, Lilian Daniela Correa. Cleber simply considers himself to be the father of three girls. Ever since he married Lilian, he has shared the child care and domestic work equally with her.

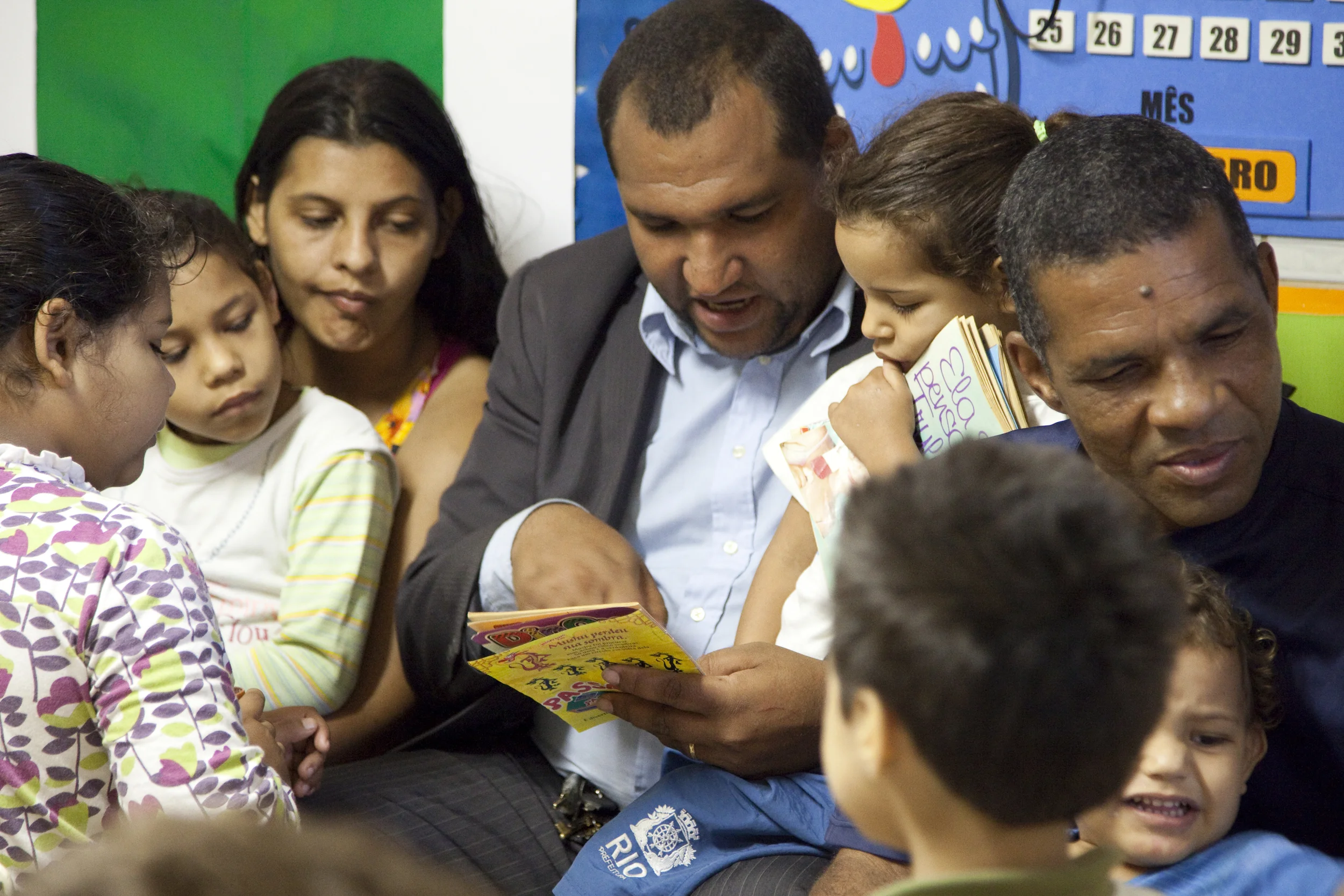

Cleber was also one of the participants in a series of father-training workshops on parenting and caregiving conducted by Promundo in partnership with the Stella Maris Daycare Center in 2014. These workshops brought together parents of children attending the daycare center to address issues such as fathers’ involvement in maternal, newborn, and child health; the equitable division of child care and domestic work between fathers and mothers; and the prevention of corporal and humiliating punishments. The workshops were based on the methodology of Program P: A Manual for Engaging Men in Fatherhood, Caregiving, and Maternal and Child Health,2 which was developed by Promundo, CulturaSalud, and REDMAS.

“I started to participate in the workshops and change came fast. I started to care for [my son] in a new way, to give him more affection and to spend more time with him. Before, I did not take care of him. I thought [my job] was only to work, to put food on the table. But no, he needed more. Today I am a new person; since I started treating him like this, I’ve seen how my son has changed. Today he hugs me and tells me that he loves me all the time.”—Widson Rosa Silva, father of 5-year-old Isaac

Bringing together fathers like Cleber, who were already actively participating at home, and fathers like Widson, who gradually changed their perspective about the importance of being involved, the workshops proved to be a safe space for men to exchange positive experiences related to their roles as fathers and caregivers.

Motivated by their exchange of experiences, the group of fathers felt the need to bring these messages about men’s role in caregiving to the broader community. Together with Promundo staff, the fathers and mothers participating in the workshops mobilized to bring what they had learned to the Assis Valente Family Clinic, calling for the clinic to take action to involve men in both self-care and maternal, newborn, and child health.

Participants also announced to the Residents Association of Vila Joaniza the adaptation and launch of the Você é meu pai (“You are my father”) campaign,3 with posters that highlighted the experiences of gender-equitable and non-violent parents from within the community. The campaign was launched in October 2014, reaching approximately 10,250 people through the Assis Valente Family Clinic and the Stella Maris Daycare Center.

Guilherme Costa, Director of the Assis Valente Family Clinic, says community mobilization and campaigns is the right path to take:

“Public participation, in general, is one of the pillars of our health care system. So, when we see that the community itself is interested in motivating health providers to [promote men’s engagement], I think we’re headed in the right direction. [Right now], we see a low rate of participation by men in their partners’ prenatal visits. We hope that through this project, or perhaps through some of the workshops that we conduct with this group or the work that we are carrying out, we can begin to change that.”—Guilherme Costa, Director of the Assis Valente Family Clinic

In fact, one of the primary focuses of the community’s mobilization efforts was prenatal care, since men’s participation in prenatal visits can serve as an important gateway to their future involvement in health and caregiving. According to the International Men and Gender Equality Survey (IMAGES),4 men raised by positively involved fathers tend to have more gender-equitable attitudes as adults.

For Cleber, this speaks to the positive impact that the campaign has had on the community:

“The campaign launch was successful and very well-received by the community. It was nice to see people who are curious and interested in the subject. I think we’re starting to truly mobilize this community—and it is this type of transformation that I like to see.”

—Cleber Leonardo Ramos, father of three daughters

The example of Vila Joaniza illustrates a key strategy for engaging men in unpaid care work, and thereby helping to reduce inequalities between men and women in the home and in the workplace. Integrated programs that combine group education with community outreach, mobilization, and media campaigns are extremely effective in changing behavior, 5 showing how comprehensive local and national initiatives make it possible to move from individual change, such as Cleber’s and Widson’s, to cultural transformation.

Notes:

1

State of the World’s Fathers is the world’s first report to provide an exploration of men’s contributions to parenting and caregiving worldwide. To learn more, visit www.sowf.men-care.org

2

Program P: A Manual for Engaging Men in Fatherhood, Caregiving, and Maternal and Child Health was developed for use by health workers, social activists, nonprofit organizations (NGOs), educators, and other individuals and institutions pursuing the idea of “men as caregivers” as a starting point for improving family well-being and achieving gender equality. It identifies best practices in engaging men in maternal and child health, caregiving, and preventing violence against women and children. Learn more at http://www.promundoglobal.org/program-p

3

Created by Promundo, the Você é meu pai (“You are my father”) campaign promotes the active participation of fathers in the daily care of their children, the equitable distribution of unpaid care and domestic work, and men’s involvement in caring for their own health and their family’s health. To learn more about the campaign (in Portuguese), visit http://homenscuidam.org.br/atuacoes/campanha-voce-e-meu-pai/

4 Data available at http://www.promundoglobal.org/images

5

This and other evidence of change from interventions for men can be found at http://promundoglobal.org/resources/engaging-men-and-boys-in-changing-gender-based-inequity-in-health-evidence-from-programme-interventions/